Photos by Bill Heimbrock

We had a warm pleasant day for the second field trip in a row. Our luck is returning. Our choice this month was a long gentle slope on a roadside southeast of Florence, KY. The site exposes the McMillan formation, where we can find a wide variety of uncommon fossils along with an abundant supply of common Maysvillian fauna. As you can see from the photos below, the site was grassy with plenty of late Ordovician rock and clay poking out everywhere. The age of the fossils are about 445 million years old.

Fossils Found at Site #1

Brachiopods

Brachiopods were by far the most abundant fossil on this site,

even out-ranking bryozoans. These rubbly limestone layers represented

accumulated shell beds.

The most abundant brachiopod was various species of Vinlandostrophia, formerly called Platystrophia.

The first species we found was Vinlandostrophia cypha. Shown in the next 3 photos below, it is identified by having one strong plication (ridge) in the sulcus (Indentation in the center).

The next species of brachiopod we found in large numbers was Vinlandostrophia ponderosa. This brachiopod is the largest of the Cincinnatian articulate brachiopods. It is described as having 3 large equal plications in the sulcus. (next 2 pictures)

Do you notice something in the last brachiopod above? There is a fourth plication

(ridge) in the sulcus (indentation). If you look at the back of the brachiopod,

you see it starts off having 3 plications and then it splits into four.

Here are 3 more specimens from this site. Count the plications in the sulcus.

| Specimen #1: Classic

Vinlandostrophia ponderosa 3 strong plications in the sulcus     |

Specimen #2: 3 strong and 2 weak plications in the sulcus.

|

Specimen #3: 3 strong and 3 weak plications in the sulcus.    |

Confused? Don't be. These are all one species - Vinlandostrophia ponderosa. I think the bifurcation (splitting) of plications (creases) happen as the animal gets older.

One member collected a very nice fragment if Vinlandostrophia ponderosa.

This is the inside surface of one valve and it clearly shows the deep muscle

scar that is an easy way to identify the species of a brachiopod. THIS is what

you want to collect when fossil hunting in the Cincinnati area. Awesome.

Something else that is awesome is this find. It looks to be an "open"

brachiopod. If that's what is happening, it means the brachiopod died with the two valves hinged open.

It's death was apparently quite a surprise!

This site also had an unusual abundance of the brachiopod,

Hebertella sp. .

Oddly, most of the the Hebertella found on this site had a deep sinus.

Just the same, they are probably the common species Hebertella

occidentalis. (next 5 photos representing 3 specimens).

Perhaps the Hebertella's sinus or fold gets deeper

as the animal gets older. Here's what we think is a small, young Hebertella

found that day.

There is a slight wavy shape to it, but not much. (next 3 photos).

It may not seem like it, but the most abundant brachiopod on this and all

the fossil sites in the Cincinnati area is the tiny Zygospira sp. The ones found

on this site were larger than I've seen on most sites. Here's a single

specimen with scale.

We also found large numbers of the brachiopod

Rafinesquina ponderosa (next 3

pics).

When you are a Dry Dredger, you learn to collect meaningful fossils. The

specimen below is a single pedicle valve showing the internal features of

Rafinesquina ponderosa. This fossil provides knowledge

of this animal. Once again, awesome.

Here is the best find of the day in my opinion. It's an inarticulate brachiopod

named Schizocrania filosa attached to

an articulate brachiopod, Rafinesquina sp.

What is more remarkable is that the top valve (shell) of this

Schizocrania is weathered away, exposing the bottom valve that was

attaching to the Rafinesquina. This is hardly ever seen. Very nice! (next 2

pics)

Another inarticulate we found that is MUCH more common is Petrocrania scabiosa.

Shown below with the lower red arrow pointing to it, these inarticulates attach

mostly to Rafinesquina also.

Notice also the upper

red arrow. It points to something a bit more interesting - a colony of tiny

annelid tube worms called Cornulites. A close-up is shown in the subsequent

photo.

Okay, showing calcite crystals may seem off-topic, but brachiopods are preserved

almost entirely in calcite. These are typical fragments of Vinlandostrophia ponderosa

with calcite crystals inside, as if they were a geode. No

brachiopods were harmed in the making of this field trip report. There were

plenty of already-broken brachiopods on this fossil site. (next 3 pics).

Nautiloid Cephalopods

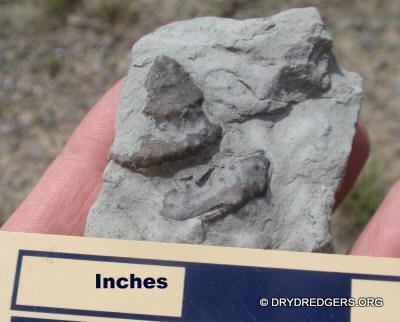

Today's location was a good one for nautiloid cephalopods. Here's a fragment

showing both sides. It is preserved as a partial internal mold. (next 2 pics)

This next cephalopod fossil is especially nice because you have both the

internal mold of some of the chambers as well as the external mold. Take a look

and you will see what I mean.

Here's a cephalopod with brown calcite covering some of the chambers. The

chambers are filled with 445 million year old silt. Overtop of it all is a hash

of fossil bits that probably represents what the debris on the sea floor looked

like at the time. All this on one fossil!

That combination of preservation was not uncommon on this McMillan Formation

hillside. Here are a couple more cephalopod specimens preserved in more than one

way.

And here's an odd circle shape that might be a mystery on other fossil sites.

With the abundance of nautiloid cephalopods, this is probably a large segment of

cephalopod filled with bryozoans and silt. Now, was this fragment of cephalopod

resting on the sea floor horizontally or vertically? There are clues in the

fossil.

Gastropods (Snails)

The results are in. There were more empty shells of snails

from this century than there were infills of Ordovician gastropods.

Here's a gastropod that was encrusted with bryozoans. The

bryozoans helped preserve it as a fossil.

The gastropods in the next 2 photos, however, were preserved

by nothing but silt and mud that filled in the snail.

Pelecypods (bivalves / clams)

This was a great clam site. Here are both sides of a nice sized clam called

Ambonychia sp.. Notice the ribbing texture from this clam.

Here's an internal mold of an Ambonychia sp. that was

not so well preserved, but the ribbing of the shell is still visible.

Another pelecypod we found was the winged clam Caritodens sp.

This next clam is an internal mold with no distinguishing surface features.

This clam does have a bit of distinguishing features, but not enough for a good

identification. It's an internal mold.

Trilobites

Unlike our last visit here in September 2015 (site #2) , no whole trilobites were found. But decent numbers of fragments of two species of trilobites were collected.

The first and most common was

Flexicalymene sp. The first 2 photos show the inside (first)

and outside of the pygidium (tail) of the Flexicalymene

trilobite.

Here's a photo of a slab that has a couple of fossils with a shape you may have

seen before but didn't know what it was. These are individual thorax segments of

Flexicalymene sp.

In this next photo, the surface of a slab has an inverted glabella of

Flexicalymene sp.

The other two brown objects in the photo above are fragments of the trilobite

Isotelus sp.

Here's a nice find. It is one lobe of the hypostome or mouth

plate of the trilobite Isotelus sp. Both sides are

shown in the photos below.

Bryozoans

We found some large fragments of bryozoan colonies. This is to be expected in

the McMillan formation. (next 3 photos)

Ichnofossils (Trace Fossils)

On the surface of shale fragments, we wound numerous trace fossils. This first

one is called Diplocraterion. If this were a

thick piece of shale, you could look at the side and see these worms were

burrowing down into the mud forming "U" shaped burrows.

This next trace fossil is a branching feeding burrow called

Chondrites sp.,

Other Photos

There is an amusing controversy in the Dry Dredgers that you can often hear at the meetings. In what do you place your fossils when collecting in the field or road cut. Do you use bags? Are these bags plastic or cloth? How about using socks to store your fossils? What about a bucket or even a basket? All methods are practiced in the Dry Dredgers but each of us have our preferences.

This member has consistently used wash tubs to collect

fossils. It allows everyone to see what was found. It's always interesting to

see what's in the tub. Here is today's cache. Click the photo for an

enlargement. Enjoy!

Well, that's all for the fossils found that day. We had a second site picked out just down the road, but most were happy with this site.

We did have one non-fossil find that I will share. A member

found a deer antler. I have been fossil hunting for 30 years and have yet

to find a deer antler. Now I'm jealous. I've got to find one!

That's all for this field trip. I hope someone gives me pictures of the Penn Dixie field trip in June. I won't be there. :-(

Now let's see the September 2018 picnic/field trip with the KPS

Back to the Field Trip Index Page

Return to Dry Dredgers Home Page

The Dry Dredgers and individual contributors reserve the rights

to all information, images, and content presented here. Permission to reproduce

in any fashion, must be requested in writing to

admin@drydredgers.org.

www.drydredgers.org

is designed and maintained by Bill Heimbrock.